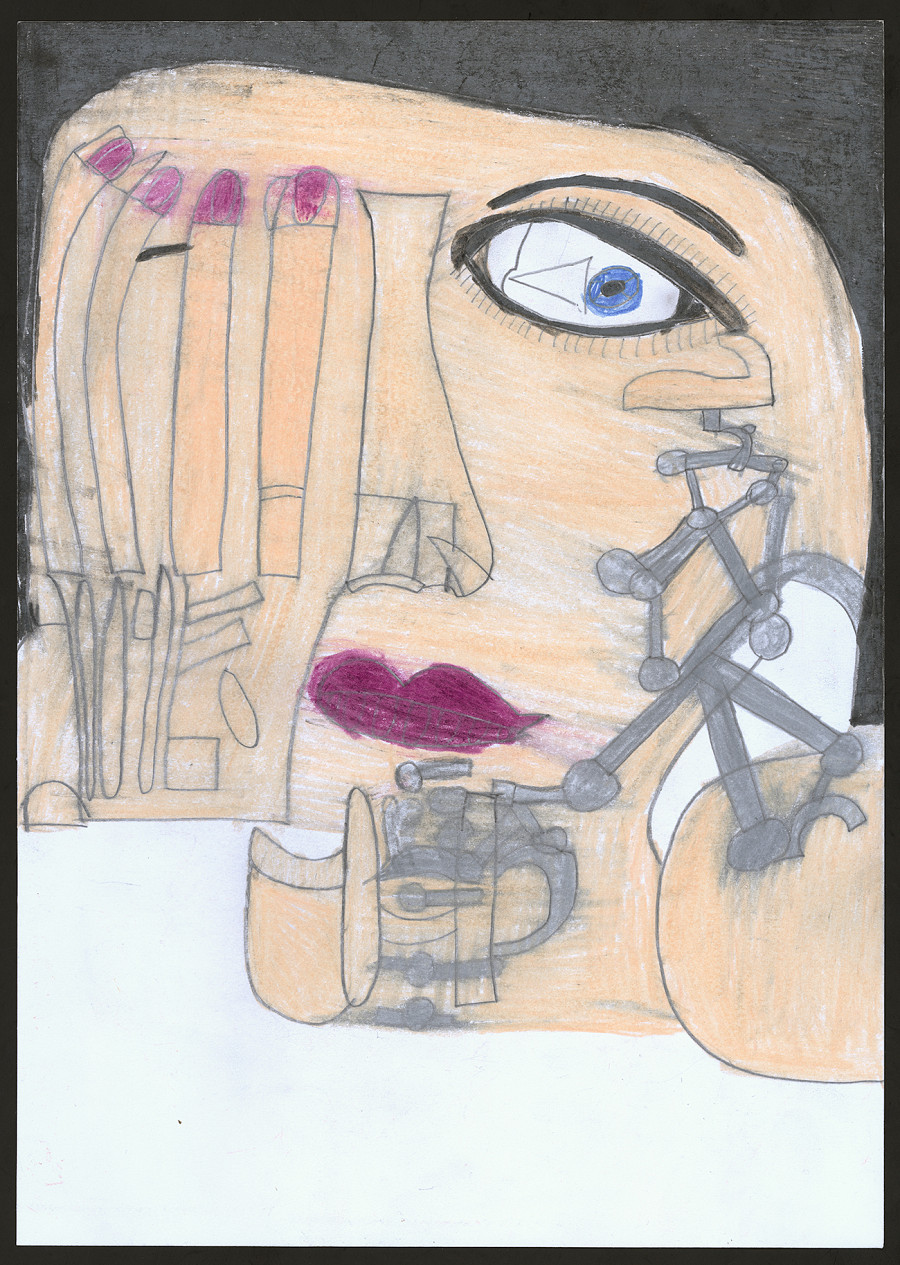

Judith Scott

Sculpture

de Judith Scott

Written by Lucienne Peiry in Le Carnet

29 mai 2013

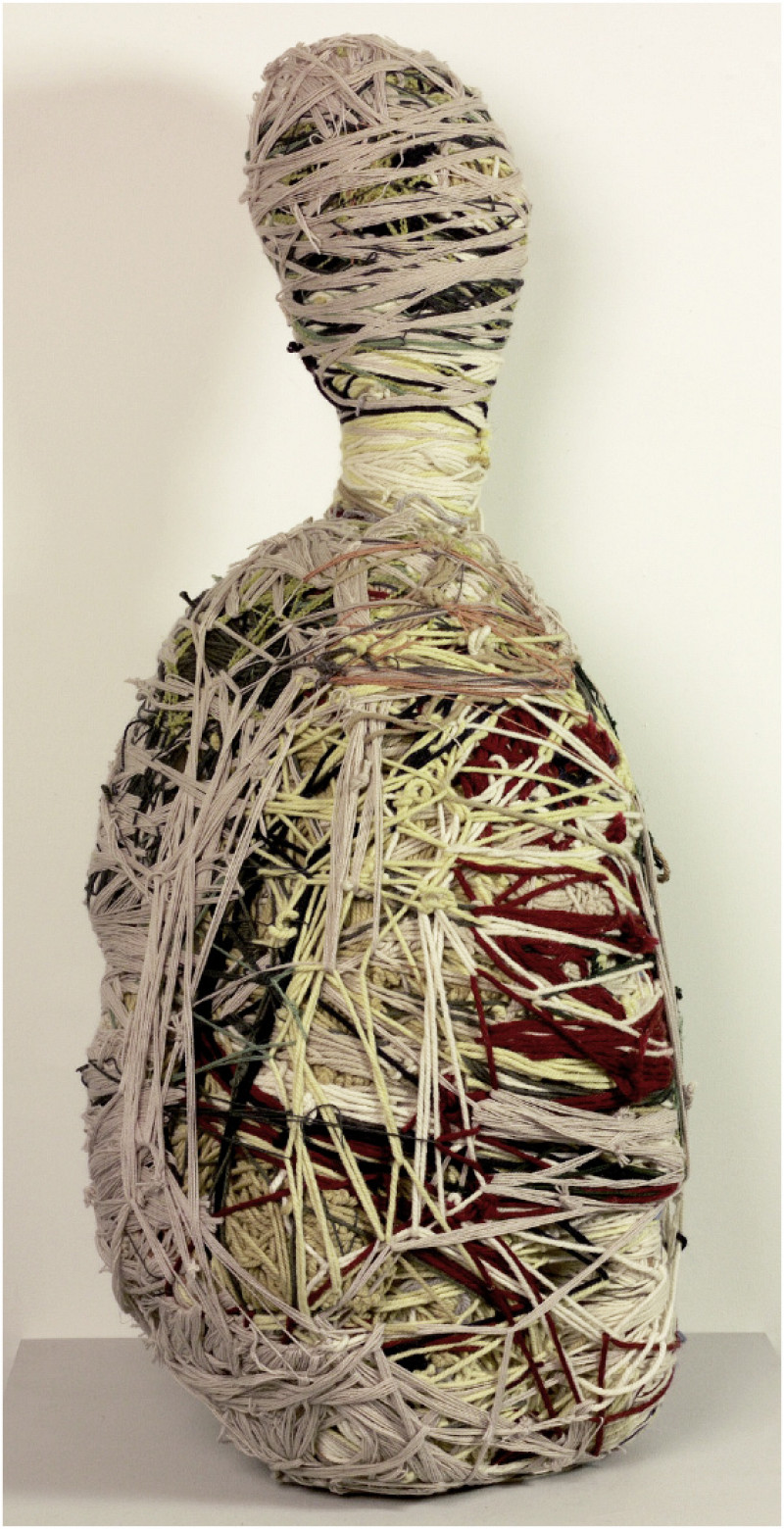

The textile works of Judith Scott are endowed with an intense power of expression: they resemble giant multicolored cocoons and are also reminiscent of voodoo dolls. Above all, they are evocative of magical fetishes and seem to hold a special connection to life and death. These sculptures conceal a secret that their author always took great care to hide. Before we examine the nature and significance of these singular works, as well as the creative process underlying their production, it is important to become acquainted with their author’s life.

The birth of twins was totally unexpected and therefore a shock to the parents, Lillian and Wallace Scott, who were doubly surprised by their premature arrival on the first day of May 1943. Judith emerged after Joyce, in Cincinnati, Ohio, in the United States. No one realized that she had Down syndrome for several months, and it was only many years later that her deafness and muteness were recognized [1].

Joyce and Judith spent their first years within a harmonious familial atmosphere, alongside their parents and three older brothers. The twins were linked by tremendous complicity and, although they lacked any common verbal language, they wove close, privileged ties thanks to their own, largely sensory ways of communicating [2]. They were inseparable and played together from morning until night, living in close touch with nature, coming and going in the house and the large garden, and sleeping in the same bed each night.

Joyce had begun school at the age of five, but Judith was turned away because of her disabilities. Having been mistakenly declared severely retarded, she experienced a foreshadowing of the rejection which was to come and her first separation from Joyce. Her parents became increasingly distressed and confused as time went by: the lack of information about Down syndrome, the absence of any therapeutic and learning establishments intended for these children, as well as social pressure ultimately undermined them completely. Heeding the advice of their physician, as well as their minister, they placed Judith in a state institution for the mentally retarded, in Columbus, more than one hundred miles away from Cincinnati, knowing full well that this institutionalization would be permanent. [3].

Judith Scott was thus forced to leave her loved ones, as well as the familiar, intimate universe where she grew up, without understanding anything about what was happening to her [4]. The split was both radical and brutal. She was undoubtedly distressed by her precipitous departure and forcible removal, which was followed by the unbearable absence of her family and, above all, of her sister. Overwrought, the small girl must have experienced a great sense of emptiness and grief ; her distress intensified by an annihilating feeling of exclusion and imprisonment. Cut off from her emotional bonds, projected into an unknown universe, where complete incarceration living conditions were imposed on her; deprived of any educational or learning environment, she was to spend 35 years in exile and confinement. The very limited information found in the medical files of the institutions where she stayed – wholly non-existent for a period of 21 years – are eloquent testimony to the negligence shown towards her.

Both a mother and a health professional, Joyce, in a moment of profound insight, decided in 1985 to try and become her twin sister’s guardian. After innumerable administrative and legal negotiations, she succeeded in bringing her to her home in California, where she lived with her daughters.

At the end of 1986, Judith was introduced to the Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, near San Francisco, an environment that, in time, came to perfectly suit her.[5] Here she quite suddenly began to devote herself to artistic creation at the age of forty-four. After a number of fruitless graphic and pictorial attempts, she found her form of creation and expression in organic, corporal sculpture. The unique creative process that she invented and developed by herself emphasizes the significance and importance underlying her work.

Judith Scott begins by retrieving or pilfering all sorts of disparate objects – an electric fan or an umbrella, magazines, a checkbook, keys – that went to make up the core of her compositions. She assembles them and anchors them solidly together, then surrounds them, enveloping them and entwining them with miscellaneous threads, twines, strings, ropes, and fibers so as to protect and entirely conceal the central body. For several weeks, and even several months at a time, Scott sits imperturbably at her table and works steadily to ‘grow’ her sculpture, accentuating certain forms or bulges and regularly rotating it to ensure that all its parts progressed. Initially seemingly anthropomorphic, zoomorphic or organic, the works gradually drifted and strayed away from their more figurative shape as time passed, becoming abstract in the last years. More often than not, they had no top or bottom, no front or back [6].

As can be seen in the documentary film devoted to her by Philippe Lespinasse [7], Judith Scott seldom seemed to look at the work in progress. Her eyes gazed into space and she navigated almost blindly but steadfastly on course, proceeding with slow, repetitive gestures, favoring the sense of touch above all to confer body to her sculpture as well as to evaluate its equilibrium and its stability [8].

The layering of the threads and entwinement, along with the ties and knots, generate an extraordinary complex, spider-like textile network. The works are brightly and richly brought to life via the varied colors, materials and fiber thicknesses used; but they also radiate powerful tension thanks to the firmness with which the threads and strands are pulled and interwoven. Disorder and disarray vie in originating an innovative, new technique. It is a thousand leagues from traditional textile crafts (embroidery, sewing, knitting, lace-making), which require following a pattern and imply a total abnegation of any personal initiative and imagination. To the contrary, and in perfect self-taught fashion, Scott throws herself headlong into a prodigiously free, inventive and anarchic process.

As soon as Judith considered that her sculpture was finished, she lost interest in it, and was neither preoccupied by its future nor its conservation, impatient as she was to devote herself to elaborating the next piece. It does not appear that her work was directed by either intention or plan and she clearly showed no desire for recognition or approval. It is quite obviously the creative process itself – the time spent in production – which Judith Scott favored. However, there is no doubt but that the sculptures themselves play an essential role in embodying the physical presence – that of ‘the other twin’ – throughout the feverish act of creation [9].

Judith Scott’s approach thus involved a process that may seem paradoxical because, on one hand, it consisted of dissimulating and concealing, and on the other hand, of growing and shaping. In the symbolic adventure she chose, Scott concealed and created all at once.

The emotional and physical reunion with her sister led Judith Scott to recover an identity, and then to develop an intimate experience at a fantasy level where she sublimated the tearing apart of which she was a victim.

Although normally an artist creates a work of art, it is the work that creates the artist in Outsider Art. For almost twenty years [10], urged on by a centripetal energy, Scott ceaselessly mummified a being by wrapping it up carefully. This stolen body, this missing body, which was taken from her, seems to metaphorically be interred by her like a deceased loved one. At the same time, she brings into being works that also seem to contain life, like cocoons. The ritual she thus plays out simultaneously recreates an enshrouding as well as a resurrection.

Her creativity can also be viewed as an activity of therapeutic value. It strangely recalls certain African fetishes, from Mali or from Benin, which are symbolically explained in the following terms by anthropologist, Nanette Jacomun Snoep: “Wrapping objects in layers of fabric is meant to put the body and spirit back in order again, thanks to bandaging, mending, and sewing. It is also concealing and erasing the presence that has been eclipsed from our gaze, thereby conferring greater power on the object. A sense of secrecy is thus established in this manner: the object seems to become increasingly inaccessible”[11]. The same is true of other magical objects, from Nigeria or from Congo in particular, where a form is placed in an enmeshment of knots so that the seer may “capture, and then control the powers over which they have mastery through the art of manipulation”[12]. The anthropologist concludes: “By knotting, by tying, and by linking elements together, one thus captures forces, one tames them, and one becomes restored.”

These singularly similar processes adopted by an American artist and by a Congolese seer, while within fundamentally different cultures, reveal the universality of instinctive and archaic symbolic language. Both motivated by powerful forces, they draw us into a universe that toys with “the Uncanny”.

The Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne owns eleven textile sculptures by Judith Scott, which form a very representative corpus of her craft of 121 pieces. These works were mainly donated by Tom di Maria, the director of the Creative Growth Art Center. When Judith Scott died – in the arms of her sister Joyce – in 2005 at the age of 62, Tom di Maria decided to give the last work by the artist to the Lausanne museum – differing from all previous pieces in that it is a composition made of just one color of wool yarn: dark anthracite.

© Lucienne Peiry, Art Historian, PhD

Director of Research and International Relations

Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne (Switzerland)

www.notesartbrut.ch/www.artbrut.ch

Ce texte vient de paraître en français dans L’Art Brut no 24, Lausanne, Collection de l’Art Brut, 2013 (en vente à la librairie du musée).

[1] See the research study by John M. MacGregor (the first and main commentator on J. Scott): Metamorphosis. The Fiber Art of Judith Scott, Oakland, Creative Growth Art Center, 1999. Some of the information included in this article is taken from conversations with Joyce Scott, as well as from e-mail exchanges with her from 2009 to 2012.

[2]. See “Conversation with Joyce Scott” by James Brett, in Museum of Everything, Exhibition 4.1, 2011, pp. 3-11. Also see the autobiography (shortly to be published) by Joyce Scott, The Colors of Gone (manuscript archives of the Collection de l’Art Brut).

[3] Judith was subjected to the fate experienced by the vast majority of children with Down syndrome, or suffering from a comparable disability, at that time. Subsequently, the equilibrium of the Scott family was broken. The mother became ill with depression that required hospitalization, while the father suffered a heart attack that made him into an invalid. He died prematurely four years later. The family was then left in a precarious financial situation.

[4] Joyce herself was neither prepared for the departure of her twin sister, nor even informed about it.

[5] The Creative Growth Art Center, headed by Tom Di Maria, is a place for self-expression intended for people affected by mental, neurological or psychiatric disorders. The center is independent of any hospital and is run entirely autonomously. A variety of art forms, painting, and sculpture are offered, without ever being imposed or guided.

[6] The retrospective organized by the Collection de l’Art Brut, in 2001 quite naturally favored works that were suspended in space so the public could appreciate them from various vantage points.

[7] Judith Scott engaged in very close ‘hands on’ relationships with her works. Always seated at a table to work, she only rarely got up to gain a perspective on her creation from a distance. She assessed it with her hands and favored tactile exploration and creation. See John M. MacGregor, op. cit., p. 171; see also the documentary film by Philippe Lespinasse, shot a few weeks before the artist’s death, « Les cocons magiques de Judith Scott” (“The Magical Cocoons of Judith Scott”), Lausanne/Bordeaux, Collection de l’Art Brut/Lokomotiv Films, 2006 (36 min.).

[8] When Tom di Maria gifted her with several magazines, I remember that she accepted the present eagerly, without looking at it, but by touching, sniffing and licking the paper. Being deaf and mute, these are the senses that she developed with her twin sister during her early childhood.

[9] See John Macgregor, op cit,

[10] Judith Scott worked at the Creative Growth Art Center from 1986 to 2005, the year of her death. Her last work was entirely crafted using black wool yarn; it is in the Collection de l’Art Brut.

[11] Nanette Jacomun Snoep, “Objets et gestes” (“Objects and Gestures”), in Recettes des Dieux. Esthétique du fétiche (Recipes of the Gods. Aesthetics of the Fetish), Musée du quai Branly, Arles, Actes Sud, 2009, p. 16.

[12] Ibid, p 22.